Pray anything¶

The Simpsons has a reputation for having jokes about maths and science. With hidden references to Fermat's last theorem and the expansion of the universe, there is a Simpsons quote for every situation. It should then be no surprise that there is one about aerosol-cloud interactions.

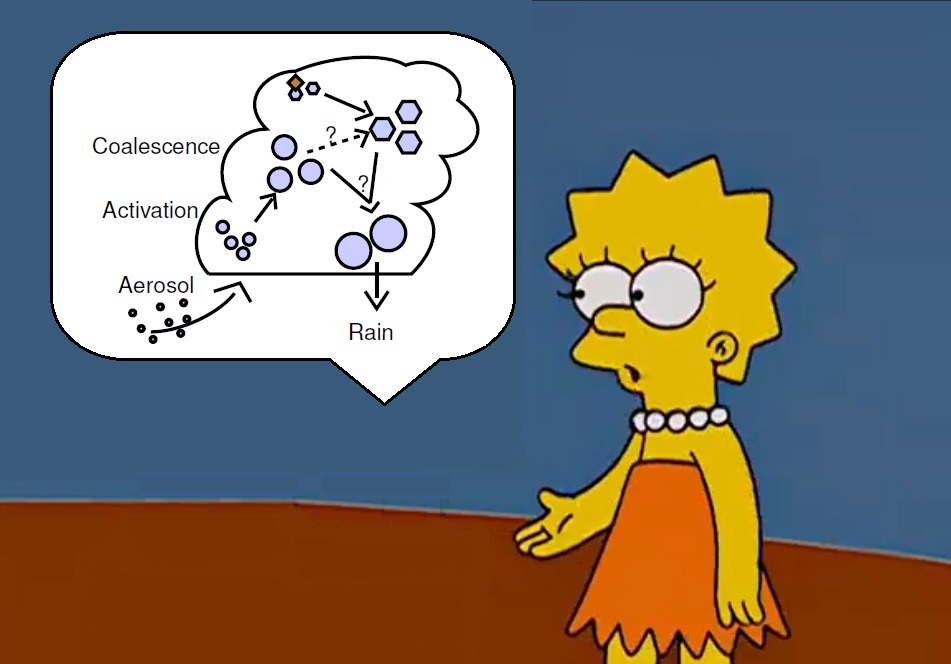

The Simpsons episode 'Pray Anything' - Season 14 Episode 10 (20th Century Fox)

In the episode 'Pray Anything (S14E10)', Homer is holding a party in the church. Like all the best parties, this involves lighting large bonfires. It starts to rain and a large flood soon forces them to the roof of the church. Homer suggests the flood is due to God's anger, but Lisa comes up with a different explanation:

''There are perfectly logical explanations for everything that happened. The bonfire sent soot into the air, which created rain, and with all the trees cut down, a flood was inevitable.''

This is one of my favourite Simpsons quotations, it is even in my thesis (I was very proud of this at the time...). But is Lisa right? Does smoke cause clouds to rain?

Lisa explains how smoke aerosols invigorate convective clouds

Convective clouds¶

First off - given the amount of lightning coming from these clouds, we are talking about clouds formed in strongly rising columns of air - convective clouds. There are lots of studies looking at how aerosols might increase rain from stratiform (layered) clouds, through glaciogenic cloud seeding. However, these studies are not really applicable to the tall convective clouds we see on screen.

Homer demonstrating this is likely a convective cloud

Smoke and rain (or rain and smoke)?¶

So how does smoke aerosol affect convective clouds? Smoke aerosol is typically anti-correlated with the occurrence of convective clouds - where there is more smoke, there is less cloud. One explanation is that smoke absorbs sunlight, heating the surrounding air and making it harder to form clouds (burning them away).

On the other hand, clouds also affect aerosol. When it is cloudy, it is more likely to be raining, which puts out fires and limits how much smoke is released. Maybe rain limits smoke, rather than smoke limiting rain?

Whichever is true, both of these explanations imply less rain when there is lots of smoke. Does this mean Lisa is wrong?

Clouds to the north, smoke to the south. Is that smoke stopping clouds from forming? (based on Koren et al., Science, 2002)

Convective invigoration¶

Not entirely. It turns out aerosols may also be able to increase the strength of thunderstorms, an effect known as convective invigoration. When there is more aerosol around, you often see more rain, not less! It is not clear how big this invigoration effect is, as both aerosols and rain are very difficult to measure from space [1]. This effect is easier to see when there is only a little bit of smoke, before the 'cloud burning' effect becomes important.

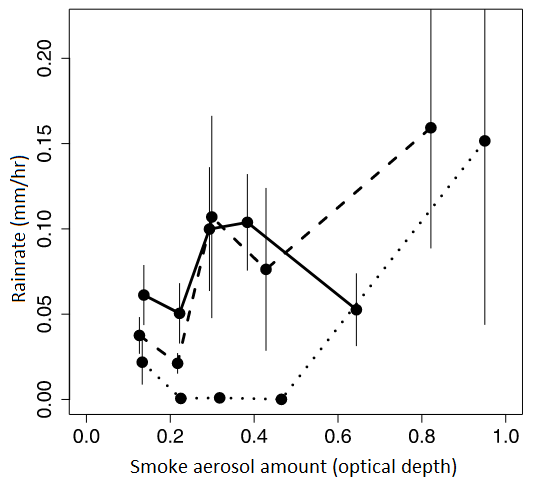

As smoke levels increase over the Amazon in 2003, (moving to the right), more rain is observed (from Lin et al, J. Geophys Res., 2006).

This convective invigoration effect has been the focus of intense study over the last few years, but some of the earliest references to it come from 2002, the same time as this episode of the Simpsons [2]. Does this mean Lisa keeps up to date with the latest issues of the Journal of Geophysical Research?

Overall rating: 9/10¶

State of the art (Lisa keeps up to date with the latest science)

Lisa delivers a lecture on cloud microphysics

Comments by email

Notes¶

| [1] | Satellite observations of aerosol increase in humid environments, where it is also more likely to rain. This make it difficult to identify the impact of aerosol on rain (see. Boucher and Quaas, Nat. Geosci., 2012 for an example). |

| [2] | The idea that aerosols could increase the strength of convective storms dates back to at least Williams et al., J. Geophys. Res (2002). There were clearly earlier ideas in this area related to cloud seeding and aerosols had long been given as a potential reason for the more intense convection found over land when compared to the ocean (e.g. Squires, Tellus 1958) |