Observing the invisible¶

The Earth is a very cloudy place. These clouds are an important control over how much sunlight the Earth reflects back into space, keeping the Earth cool. This means that a small change in the amount or properties of clouds can have a large impact on the climate.

Earthrise – the clouds are easy to see in daylight, but invisible at night. (NASA)

Since 1970s, it has been known that human are changing clouds by adding small particles (known as aerosols). Each cloud droplet forms on an aerosol particle (most of which are from natural sources, such as desert dust or sea salt). As human activities (particularly the burning of fossil fuels) emit extra aerosols [1], clouds today have more droplets in them than they would have done 200 years ago (before the industrial revolution).

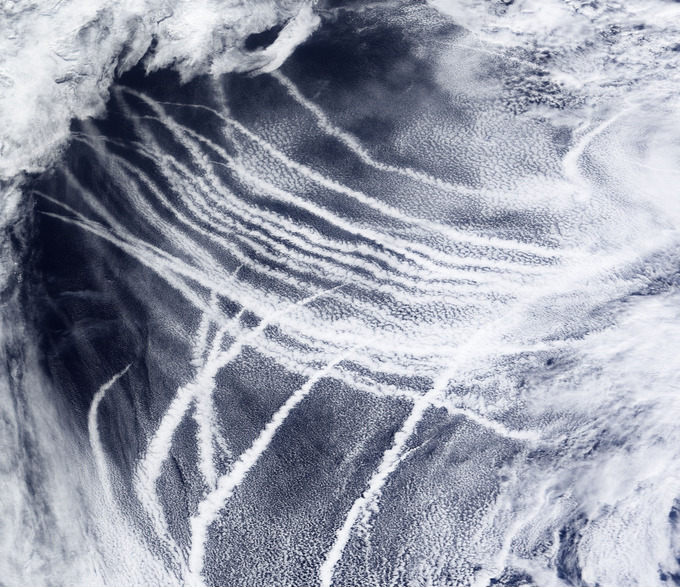

Sharing their water amount across more droplets, polluted clouds have smaller droplets on average. This could lead to a couple of possible effects - one of these is that smaller droplets are less likely to grow large enough to form rain. This might lead to an increase in cloud amount and water content, but our observations of this are limited. Evidence from ship emissions of aerosol (like the image below) suggest that stratocumulus clouds are sensitive to aerosol, and we think that increases in aerosol might mean more stratocumulus cloud.

Ship tracks (the bright white streaks in cloud behind ships) are a clear visual example of how particulates - known as aerosol - emitted by humans are modifying clouds. (NASA).

Stratocumulus¶

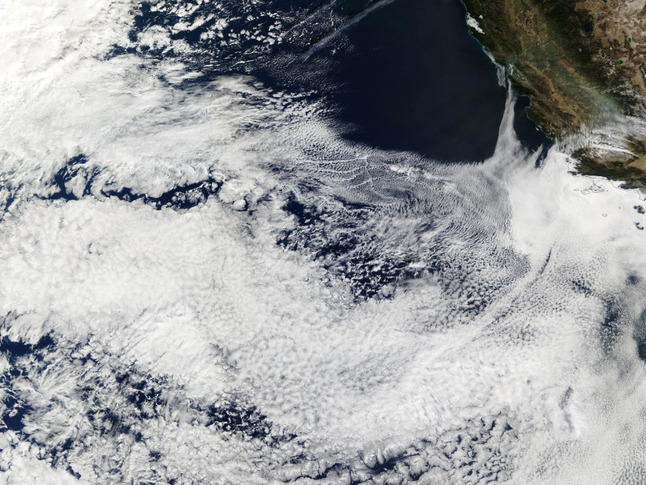

Stratocumulus clouds cover large amounts of the Earth's oceans, particularly off the western coasts of continents – this alone means that a small change in their properties could have a large climate impact. Even better, they are close to the ground (where the aerosols are emitted from) and are often found in clean regions of the globe (so even a small amount of aerosol pollution can have a large impact on their properties).

Stratocumulus clouds, off the coast of California viewed from space. They are very bright compared with the dark ocean below making them highly efficient reflectors of solar radiation. You can see the multiday break up as it gets less cloudy further away from the coast (NASA)

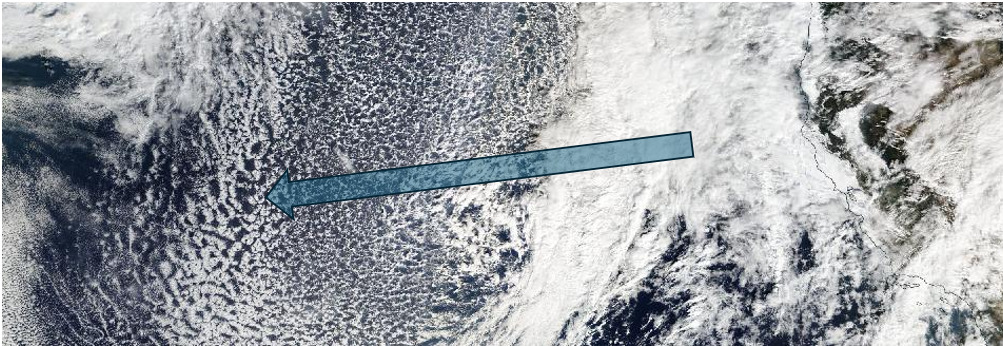

These clouds evolve over time. They are typically blown away from the coastline, where they are almost overcast. They move away from the coast and west over the open ocean over the period of a few days, gradually breaking up as they do. We think that rain is important for this breakup [2] – so if these clouds are raining less (perhaps because they are more polluted), it might slow the overall breakup and increase the amount of stratocumulus cloud.

Stratocumulus clouds over the north-east Pacific breaking up as they travel further west (left) away from the coast (NASA)

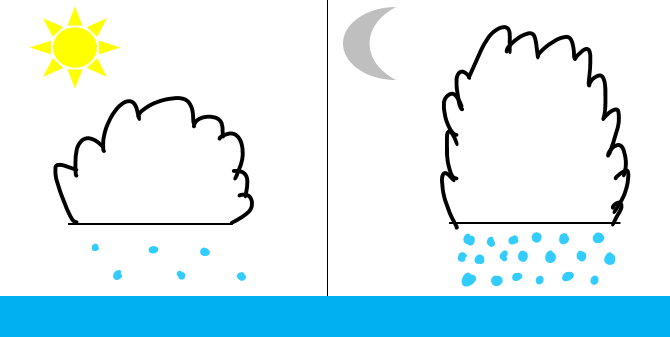

Stratocumulus clouds have a strong diurnal cycle – their behaviour is different in the day and the night. Broadly, these clouds break up during the day and reform during the night. If aerosol pollution is preventing cloud breakup, we might then expect them to have the biggest impact on cloud during the day (changing the clouds when they are breaking up).

There is a problem with this theory though - while we see lots of evidence that adding aerosols reduces rain and that this can increase the amount of cloud, stratocumulus clouds don't really rain much during their daytime breakup phase. You can't use aerosols to reduce the amount of rain if there was none to start with!

It turns out, the answer to this problem lies at night. It just difficult to see (because it is dark...).

Seeing in the dark¶

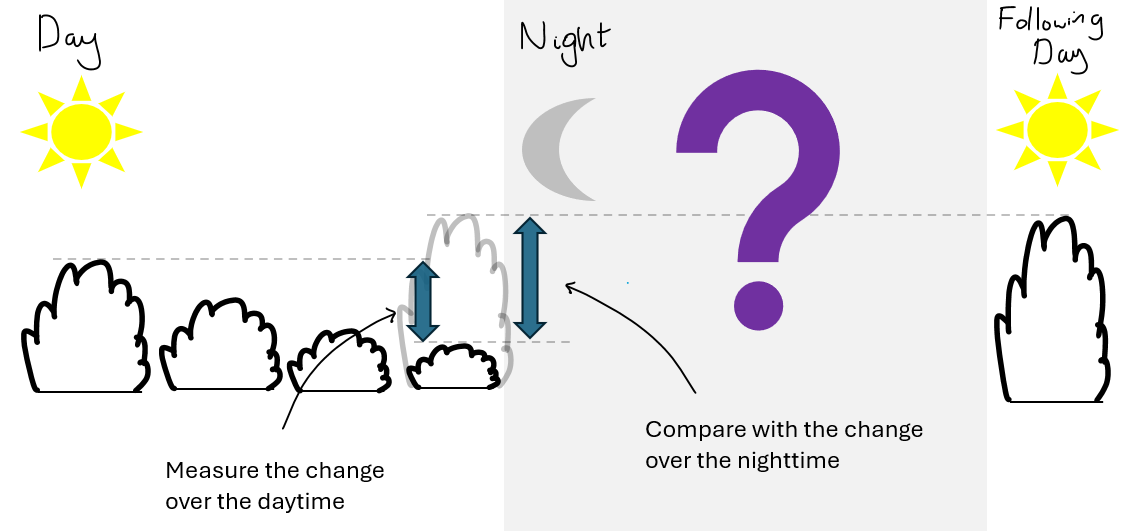

The lack of visible light during the nighttime makes observing many properties of these clouds very challenging [3]. What can be done however, is observing them at the start and end of the nighttime when we can measure their properties using reflected sunlight and using this to make inferences about their nighttime behaviour. This is much like putting your clothes in the washing machine and deducing that they have been washed by the change in their smell and wetness but without having to stick your head inside the machine whilst it is on!

An illustration of how clouds nighttime behaviours can be inferred without having to directly observe it

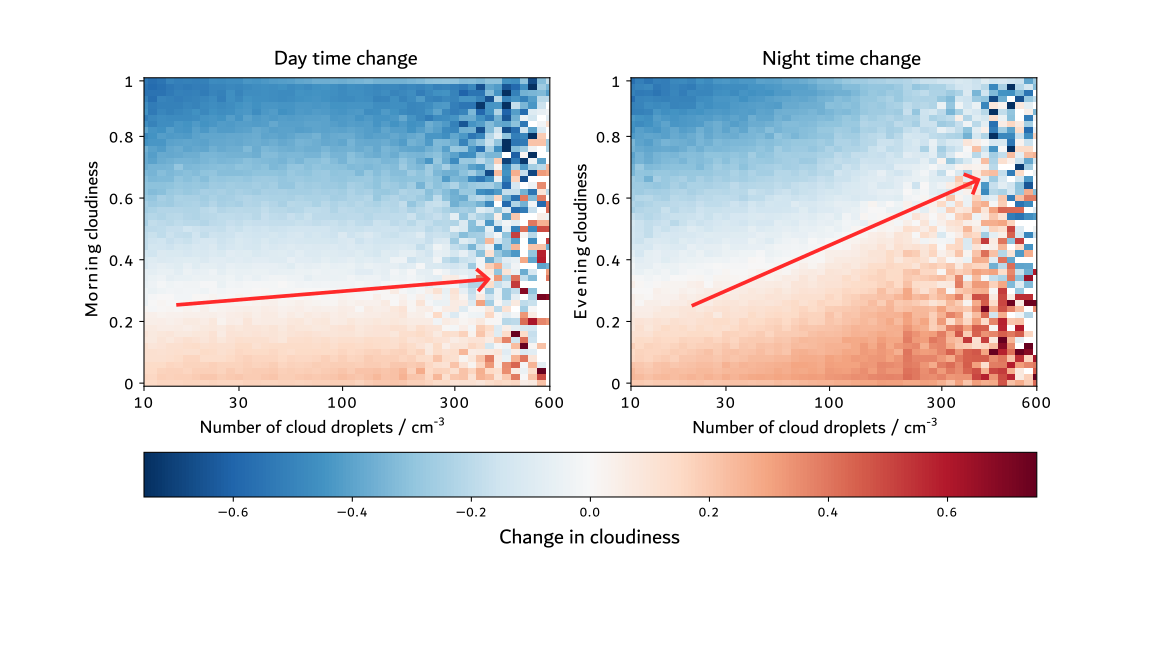

If we separate out the aerosol impact on the daytime (dawn to dusk) vs nighttime (dusk to dawn) change in cloud amount, we find that over the day, aerosols have almost no effect. Despite this being the period when the clouds break up, it seems that aerosols have very little impact! Rather surprisingly, we see a strong impact of aerosols at night instead – in polluted clouds, the cloud recovers much more effectively at night.

The red arrow below shows the point at which cloudiness goes from increasing to decreasing (red to blue). During the nighttime this is much more sensitive to the number of cloud droplets compared with the daytime (highlighted by steepness of the line; Pugsley et al, 2025

This means that although aerosols slow the cloud breakup process, they don't do it through changes in the actual daytime breakup – instead they are helping the cloud recover at night.

What is going on at night?¶

These nighttime processes are different to the daytime. In particular, stratocumulus clouds are known to rain more during the nighttime. This is because when there is less sunlight warming the top of the cloud it can grow thicker, and it is therefore more likely that a cloud droplet will grow big enough to fall out of the cloud as rain.

The thicker nighttime cloud is more likely to rain

This 'thickening' of the cloud helps them recover at night after the daytime breakup, but it is not a complete recovery (so the stratocumulus breakup and become cumulus over the course of several days). By helping this nighttime recovery, adding aerosols increases the overall cloud amount [4].

Why is the nighttime important?¶

We started off by saying that stratocumulus clouds were important because they reflect a lot of sunlight and keep the Earth cool. One of the key properties of night is that there is no sunlight, so why does this nighttime change matter? Like people, the clouds’ state in the morning has a stronge influence on their daytime behaviour. It is processes that happen during the night that set the cloud state in the morning.

Getting this right is vital if we want to accurately simulate the human impact on climate with climate models. The impact of aerosol is the most uncertain component of the human forcing of the climate, mostly due to the difficulty in simulating how clouds work. The results here show that rain is vital for this - so important that we can only see an effect when the clouds are raining most!

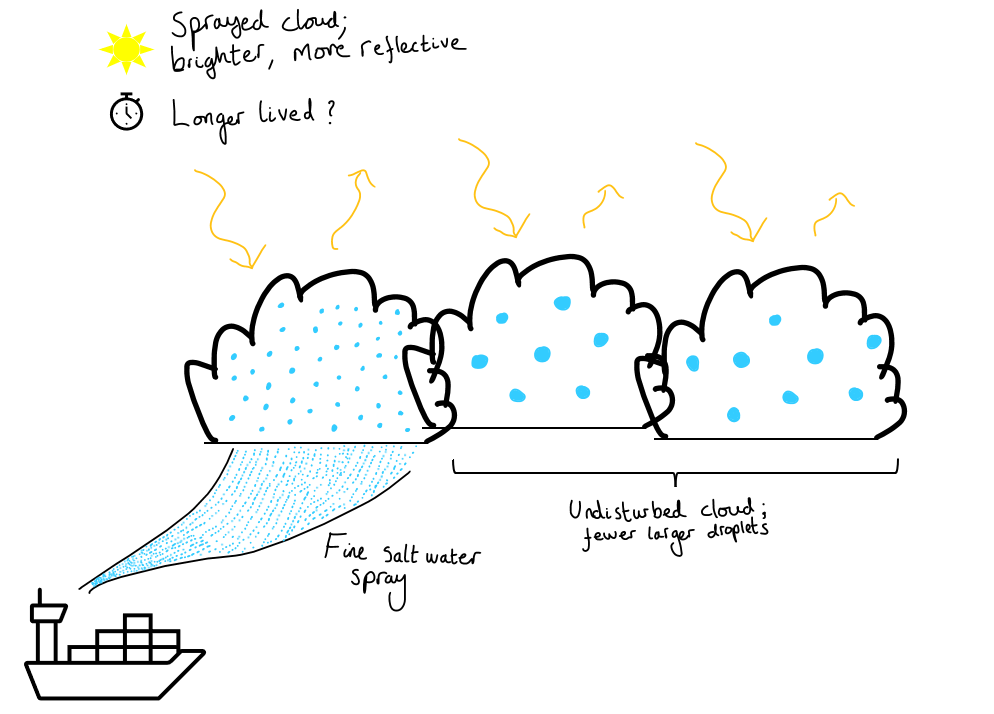

Spraying a fine salt mist into clouds may increase the brightness and lifetime, but the strength of this effect will depend on the time of day.

This is also important if you want to modify clouds on purpose - some studies have suggested that spraying aerosols into clouds could artificially brighten them. Knowing which clouds to target is essential for this. If you targeted the daytime breakup (trying to slow it), you would get a much weaker response compared to trying to increase the nighttime recovery of the clouds!

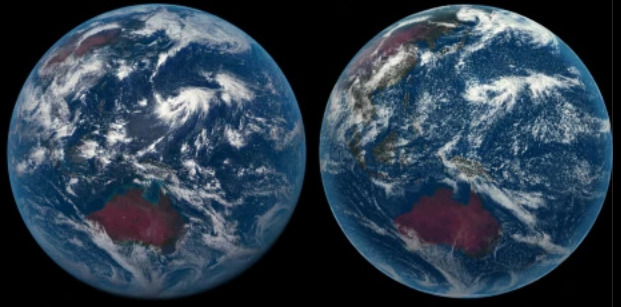

One of these is a real Earth, the other is a climate model (Stevens et al, 2019).

This also matters for checking our climate models. An important job for climate models is to simulate the future. We don't know exactly what the future will look like, but we expect clouds to work the same way. If we are to trust climate models, we need to know that the clouds in climate models work in the same way as those in the real atmosphere - they are right for the right reasons. This means they have to properly simulate both the daytime and the nighttime impact of aerosols, they have to understand the secret life of clouds.

Thanks also to Vishnu Nair (Imperial College London) who worked with us on this research

Comments by email

Notes¶

| [1] | Many of these aerosols are actually 'secondary' aerosols - human activity doesn't emit the aerosol directly, but it does emit the precursor chemicals (such as SO2) that then go on to form the aerosols. |

| [2] | This is not the only factor (Burleyson et al, 2013), but it is important for proposed aerosol impacts on cloud. A selection of modelling studies have shown that it is difficult to maintain a stratocumulus cloud once rainfall gets properly started (Goren et al, 2019). |

| [3] | You can see clouds at night with infrared, but this depends on having a good contrast (i.e. a different temperature) to the surface below. Stratocumulus clouds are very low and so are pretty much the same temperature as the surface below, making them difficult to see at night. To measure the properties of the cloud (such as the droplet number), we also need reflected sunlight (which is in short supply at night). This is not impossible though - some studies have shown you could use light reflected by the moon, but this is tricky to do in practice. |

| [4] | It turns out there is another effect that happens - aerosols help to thin the cloud, reducing the total water content of the cloud (LWP). We see a faster reduction on LWP (roughly the vertical thickness of the cloud). This likely comes through the smaller droplets in the polluted cloud supporting the more efficient evaporation of cloud water. This actually doubles the importance of the nighttime aerosol effect! |